Chickamauga Wars (1776–1794)

From ENC Phillips Group Wiki

The Chickamauga Wars (1776–1794) were a series of back-and-forth raids, campaigns, ambushes, minor skirmishes, and several full-scale frontier battles which were a continuation of the Cherokee (Ani-Yunwiya, Ani-Kituwa, Tsalagi, Talligewi) struggle against encroachment into their territory by American frontiersmen from the former British colonies, and, until the end of the American Revolution, their contribution to the war effort as British allies.

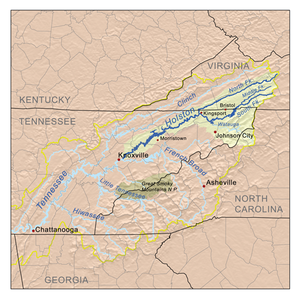

Open warfare broke out in the summer of 1776 between the Cherokee led by Dragging Canoe (initially called the "Chickamauga" or "Chickamauga-Cherokee", and later the "Lower Cherokee", by colonials) and frontier settlers along the Watauga, Holston, Nolichucky rivers, and Doe rivers in East Tennessee and later spread to those along the Cumberland River in Middle Tennessee and in Kentucky, as well as the colonies (later states) of Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia.

The earliest phase of these conflicts, ending with the treaties of 1777, is sometimes called the "Second Cherokee War", a reference to the earlier Anglo-Cherokee War, but that is something of a misnomer. Since Dragging Canoe was the dominant leader in both phases of the conflict, however, referring the period as "Dragging Canoe's War" would not be incorrect.

Dragging Canoe's warriors fought alongside and in conjunction with Indians from a number of other tribes both in the South and in the Northwest (most often Muscogee in the former and Shawnee in the latter); enjoyed the support of, first, the British (often with active participation of British agents and regular soldiers) and, second, the Spanish; and were founding members of the Native Americans' Western Confederacy.

Though the Americans used "Chickamauga" as a convenient label to distinguish between the Cherokee followers of Dragging Canoe and those abiding by the peace treaties of 1777, there was never actually a separate tribe of "Chickamauga", as mixed-blood Richard Fields related to the Moravian Brother Steiner when the latter met with him at Tellico Blockhouse.[1]

Contents

- 1 Prelude

- 2 The "Second Cherokee War"

- 3 First migration, to the Chickamauga area

- 4 Reaction

- 5 Second migration and expansion

- 6 After the Revolution

- 7 Peak of Lower Cherokee power and influence

- 7.1 Massacre of the Kirk family

- 7.2 Massacre of the Brown family

- 7.3 Murders of the Overhill chiefs

- 7.4 Houston's Station

- 7.5 Invasion and counter-invasion

- 7.6 The Flint Creek band/Prisoner exchange

- 7.7 Blow to the Western Confederacy

- 7.8 Chiksika's band of Shawnee

- 7.9 The "Miro Conspiracy"

- 7.10 Doublehead

- 7.11 Treaty of New York

- 7.12 Muscle Shoals

- 7.13 Bob Benge

- 7.14 Treaty of Holston

- 7.15 Battle of the Wabash

- 8 Death of "the savage Napoleon"

- 9 The final years

- 10 End of the Chickamauga Wars

- 11 Assessment

- 12 Aftermath

- 13 Tecumseh's return and later events

- 14 Statement of Richard Fields on the "Chickamauga"

- 15 Scots (and other Europeans) among the Cherokee

- 16 Possible origins of the words "Chickamauga" and "Chattanooga"

- 17 See also

- 18 References

- 19 Sources

- 20 External links

Prelude

If James Mooney is correct, the first conflict of the Cherokee with the British occurred in 1654 when a force from Jamestown Settlement supported by a large party of Pamunkey attacked a town of the "Rechaherians" (referred to as the "Rickohakan" by German traveller James Lederer when he passed through in 1670) that had between six and seven hundred warriors, only to be driven off.[2]

After siding with the Province of South Carolina in the Tuscarora War of 1711-1715, the Cherokee turned on their erstwhile British allies in the Yamasee War of 1715-1717 along with the other tribes until switching sides again midway, which ensured the defeat of the latter.

Anglo-Cherokee War

At the outbreak of the French and Indian War (1754–1763), the Cherokee were staunch allies of the British, taking part in such far-flung campaigns as those against Fort Duquesne (at the modern-day Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania) and the Shawnee of the Ohio Country. In 1755, a band of Cherokee 130-strong under Ostenaco (Ustanakwa) of Tomotley (Tamali) took up residence in a fortified town at the mouth of the Ohio River at the behest of fellow British allies, the Iroquois.[3]

For several years, French agents from Fort Toulouse had been visiting the Overhill Cherokee, especially those on the Hiwassee and Tellico Rivers, and these had made in-roads into those places. The strongest pro-French sentiment among the Cherokee came from Mankiller (Utsidihi) of Great Tellico (Talikwa), Old Caesar of Chatuga (Tsatugi), and Raven (Kalanu) of Great Hiwassee (Ayuhwasi). The First "Beloved Man" (Uku) of the nation, Kanagatucko (Kanagatoga, "Stalking Turkey", called 'Old Hop' by the whites), was himself very pro-French, as was his nephew who succeeded at his death in 1760, Standing Turkey (Kunagadoga).[4]

The former site of the Coosa chiefdom during the time of the Spanish explorations in the 16th century, long deserted, was reoccupied in 1759 by a Muscogee contingent under a leader named Big Mortar (Yayatustanage) in support of his pro-French Cherokee allies in Great Tellico and Chatuga and as a step toward an alliance of Muscogee, Cherokee, Shawnee, Chickasaw, and Catawba. His plans were the first of their kind in the South, and set the stage for the alliances that Dragging Canoe would later build. After the end of the French and Indian War, Big Mortar rose to be the leading chief of the Muscogee.

The Anglo-Cherokee War was initiated in 1758 in the midst of the ongoing war by Moytoy (Amo-adawehi) of Citico in retaliation for mistreatment of Cherokee warriors at the hands of their British and colonial allies, and lasted from 1758 to 1761. Moytoy's horse-stealing began the domino effect that ended with the murders of Cherokee hostages at Fort Prince George near Keowee, and the massacre of the garrison of Fort Loudoun near Chota.

Those two connected events catapulted the whole nation into war until the actual fighting ended in 1761, with the Cherokee being led by Oconostota (Aganstata) of Chota (Itsati), Attakullakulla (Atagulgalu) of Tanasi, Ostenaco of Tomotley, Wauhatchie (Wayatsi) of the Lower Towns, and Round O of the Middle Towns.

The peace between the Cherokee and the colonies was sealed with separate treaties with the Colony of Virginia (1761) and the Province of South Carolina (1762). Standing Turkey was deposed and replaced with pro-British Attakullakulla. John Stuart, the only officer to escape the Fort Loudoun massacre, became British Superintendent of Indian Affairs for the Southern District out of Charlestown, South Carolina, and the main contact of the Cherokee with the British government. His first deputy, Alexander Cameron, lived among them, first at Keowee, then at Toqua on the Little Tennessee, while his second deputy, John McDonald, set up a hundred miles to the southwest on the west side of Chickamauga River, where it was crossed by the Great Indian Warpath.

During the war, a number of major Cherokee towns had been destroyed by the army under British general James Grant, and were never reoccupied, most notably Kituwa, the inhabitants of which migrated west and took up residence at Great Island Town on the Little Tennessee River among the Overhill Cherokee.[5]

In the aftermath of the war, that part of France's Louisiana Territory east of the Mississippi went to the British along with Canada, while Louisiana west of the Mississippi went to Spain in exchange for Florida going to Britain, which divided it into East Florida and West Florida. Mindful of the recent war and after the visit to London of Henry Timberlake and three Cherokee leaders: Ostenaco, Standing Turkey, and Wood Pigeon (Ata-wayi),[6] King George III issued the Royal Proclamation of 1763 prohibiting settlement west of the Appalachian Mountains, laying the foundation of one of the major irritants for the colonials leading to the Revolution.

Treaty of Fort Stanwix

After Pontiac's War (1763–1764), the Iroquois Confederacy ceded to the British government its claims to the hunting grounds between the Ohio and Cumberland rivers, known to them and other Indians as Kain-tuck-ee (Kentucky), to which several other tribes north and south also lay claim, in the 1768 Treaty of Fort Stanwix. The land in the Ohio Valley and Great Lakes regions (the Illinois Country or, formerly, Upper Louisiana), meanwhile, later known to the fledgling independent American government as the Northwest Territory, were originally planned as a British colony that was to be called Charlotina. Plans for the new colony, however, were scuttled by the above-mentioned Royal Proclamation, and in 1774 the lands became part of the Province of Quebec. These events initiated much of the conflict which followed in the years ahead.

Watauga Association

Template:Wikisourcepar The earliest colonial settlement in the vicinity of what became Upper East Tennessee was Sapling Grove, the first of the North-of-Holston settlements, founded by Evan Shelby, who purchased the land from John Buchanan, in 1768. Jacob Brown began another on the Nolichucky River and John Carter in what became known as Carter's Valley (between Clinch River and Beech Creek), both in 1771. Following the Battle of Alamance in 1771, James Robertson led a group of some twelve or thirteen Regulator families from North Carolina to the Watauga River.

All these groups believed they were in the territorial limits of the colony of Virginia. After a survey proved their mistake, Deputy Superintendent for Indian Affairs Alexander Cameron ordered them to leave. However, Attakullakulla, now First Beloved Man, interceded on their behalf, and they were allowed to remain, provided there was no further encroachment.

In May 1772, the settlers on the Watauga signed the Watauga Compact to form the Watauga Association, and in spite of the fact the other settlements were not parties to it, all of them are sometimes lumped together as "Wataugans". [7]

The next year, in response to the first attempt to establish a permanent settlement inside the hunting grounds of Kentucky in 1773 by a group under Daniel Boone, the Shawnee, Lenape (Delaware), Mingo, and some Cherokee attacked a scouting and forage party that included Boone's son James (who was captured and tortured to death along with Henry Russell), beginning Dunmore's War (1773–1774).

Henderson Purchase

One year later, in 1775, a group of North Carolina speculators led by Richard Henderson negotiated the Treaty of Watauga at Sycamore Shoals with the older Overhill Cherokee leaders, chief of whom were Oconostota and Attakullakulla (now First Beloved Man), surrendering the claim of the Cherokee to the Kain-tuck-ee (Ganda-giga'i) lands and supposedly giving the Transylvania Land Company ownership thereof in spite of claims to the region by other tribes such as the Lenape, Shawnee, and Chickasaw.

Dragging Canoe (Tsiyugunsini), headman of Great Island Town (Amoyeliegwayi) and son of Attakullakulla, refused to go along with the deal and told the North Carolina men, "You have bought a fair land, but there is a cloud hanging over it; you will find its settlement dark and bloody".[8] The Watauga treaty was quickly repudiated by the governors of Virginia and North Carolina, however, and Henderson had to flee to avoid arrest. Even George Washington spoke out against it. The Cherokee appealed to John Stuart, the Indian Affairs Superintendent, for help, which he had provided on previous such occasions, but the outbreak of the American Revolution intervened.

The "Second Cherokee War"

In the view of both Henderson and of the frontierspeople, the revolution negated the judgements of the royal governors, and the Transylvania Company began pouring settlers into the region they had "purchased". Stuart, meanwhile, was besieged by a mob at his house in Charlestown and had to flee for his life before he could act. His first stop was St. Augustine in East Florida,[9] from where he sent his deputy, Cameron, and his brother Henry to Mobile to obtain short-term supplies with which the Cherokee could survive and fight if necessary.

Dragging Canoe took a party of eighty warriors to provide security for the packtrain, and met Henry Stuart and Cameron, his adopted brother, at Mobile on 1 March 1776. He asked how he could help the British against their rebel subjects, and for help with the illegal settlers, and they told him to take no action at the present but to wait for regular troops to arrive.

When they arrived at Chota, Henry sent out letters to the trespassers of Washington District (Watauga and Nolichucky), Pendelton District (North-of-Holston), and Carter's Valley (in modern Hawkins County) reiterating the fact they were on Indian land illegally and giving them forty days to leave, which those sympathetic to the Revolution then forged to indicate a large force of regular troops plus Chickasaw, Choctaw, and Muscgoee was on the march from Pensacola and planning to pick up reinforcements from the Cherokee. The forgeries alarmed the countryside, and settlers began gathering together in closer settlements than their isolated farmsteads, building stations (small forts), and otherwise preparing for an attack.[10]

Visit from the northern tribes

In May 1776, partly at the behest of Henry Hamilton, the British governor in Detroit, the Shawnee chief Cornstalk led a delegation from the northern tribes (Shawnee, Lenape, Iroquois, Ottawa, others) to the southern tribes (Cherokee, Muscogee, Chickasaw, Choctaw), calling for united action against those they called the Long Knives, the squatters who settled and remained in Kain-tuck-ee (Ganda-gi), or, as the settlers called it, Transylvania. The northerners met with the Cherokee leaders at Chota. At the close of his speech, he offered his war belt, and Dragging Canoe accepted it, along with Abraham (Osiuta) of Chilhowee (Tsulawiyi). Dragging Canoe also accepted belts from the Ottawa and the Iroquois, while Savanukah, the Raven of Chota, accepted the belt from the Lenape. The northern emissaries also offered war belts to Stuart and Cameron, but they declined to accept.

The plan was for Middle, Out, and Valley Towns of what is now western North Carolina to attack South Carolina, the Lower Towns of western South Carolina and North Georgia (led by personally by Alexander Cameron) to attack Georgia, and the Overhill Towns along the lower Little Tennessee and Hiwassee rivers to attack Virginia and North Carolina. In the Overhill campaign, Dragging Canoe was to lead a force against the Pendelton District, Abraham another against the Washington District, and Savanukah one against Carter's Valley.

To demonstrate his determination, Dragging Canoe led a small war party into Kentucky and returned with four scalps to present to Cornstalk before the northern delegation departed.[11]

Jemima Boone and the Calloway sisters

Shortly after the visit from the northern tribes, the Cherokee began small-party raiding into Kentucky, often in conjunction with the Shawnee. In one of these raids a week before the Cherokee attacks on the settlements and colonies, a war party of five, two Shawnee and three Cherokee led by Hanging Maw (Skwala-guta) of Coyatee (Kaietiyi), captured three teenage girls in a canoe on the Kentucky River. The girls were Jemima Boone, daughter of Daniel Boone, and Elizabeth and Frances Callaway, daughters of Richard Callaway. The war party hurried toward the Shawnee towns north of the Ohio River, but were overtaken by Boone and his rescue party after three days. After a brief firefight, the war party retreated and the girls were rescued, unharmed and having been treated reasonably well, according to Jemima Boone.

Besides the sheer determined courage of the feat itself, the incident is also notable for providing inspiration for the chase scene in James Fenimore Cooper's novel The Last of the Mohicans after the capture of Cora and Alice Munro, in which their father Lieutenant-Colonel George Munro, the book's protagonist Hawkeye (Natty Bumppo), his adopted Mohican elder brother Chingachgook, Chingachgook's son Uncas, and David Gamut follow and overtake the Huron war party of Magua in order to rescue the sisters.

The attacks

The squatters in the settlements of what was to become Upper East Tennessee were forewarned of the impending Cherokee attacks by traders who'd come to them from Chota bearing word from the Beloved Woman (female equivalent of Beloved Man, the Cherokee title for a leader) Nancy Ward (Agigaue). Having thus been betrayed, the Cherokee offensive proved to be disastrous for the attackers, particularly those going up against the Holston settlements.

Finding Heaton's Station deserted, Dragging Canoe's force advanced up the Great Indian Warpath and had a small skirmish with a body of militia numbering twenty who quickly withdrew. Pursuing them and intending to take Fort Lee at Long-Island-on-the-Holston, his force advanced toward the island. However, his force encountered a larger force of militia six miles from their target, about half the size of his own but desperate, in a stronger position than the small group before. During the 'Battle of Island Flats' which followed, Dragging Canoe himself was wounded in his hip by a musket ball and his brother Little Owl (Uku-usdi) incredibly survived after being hit eleven times. His force then withdrew, raiding isolated cabins on the way and returned to the Overhill area with plunder and scalps, after raiding further north into southwestern Virginia.

The following week, Dragging Canoe personally led the attack on Black's Fort on the Holston (today Abingdon, Virginia). One of the settlers, Henry Creswell, who had just returned from fighting at Long Island Flats, was killed on July 22, 1776, when he and a group of settlers were attacked while they were on a mission outside the stockade.[12] More attacks continued the third week of July, with support from the Muscogee and Tories.

Abraham of Chilhowee was likewise unsuccessful in his attempt to take Fort Caswell on the Watauga, his attack being driven off with heavy casualties. Instead of withdrawing, however, he put the garrison under siege, a tactic which had worked well the previous decade with Fort Loudoun, but gave that up after two weeks. Savanukah raided from the outskirts of Carter's Valley far into Virginia, but those targets contained only small settlements and isolated farmsteads so he did no real military damage.

After the failed invasion of the Holston, despite his wounds, Dragging Canoe led his warriors to South Carolina to join Alexander Cumming and the Cherokee from the Lower Towns.

Colonial response

Response from the colonials in the aftermath was swift and overwhelming. North Carolina sent 2400 militia to scour the Oconaluftee and Tuckasegee Rivers and the headwaters of the Little Tennessee and Hiwassee, South Carolina sent 1800 men to the Savannah, and Georgia sent 200 to the Chattahoochee and Tugaloo. In all, they destroyed more than fifty towns, burned their houses and food, destroyed their orchards, slaughtered livestocks, and killed hundreds, as well as putting survivors on the slave auction block.

In the meantime, Virginia sent a large force accompanied by North Carolina volunteers under William Christian to the lower Little Tennessee valley. By this time, Dragging Canoe and his warriors had returned to the Overhill Towns. Oconostota advocated making peace with the colonists at any price. Dragging Canoe countered by calling for the women, children, and old to be sent below the Hiwassee and for the warriors to burn the towns, then ambush the Virginians at the French Broad River, but Oconostota, Attakullakulla, and the rest of the older chiefs decided against that path, Oconostota sending word to the approaching army offering to exchange Dragging Canoe and Cameron if the Overhill Towns were spared.

In Dragging Canoe's last appearance at the council of the Overhill Towns, he denounced the older leaders as rogues and "Virginians" for their willingness to cede away land for an ephemeral safety, ending, "As for me, I have my young warriors about me. We will have our lands." [13][14] He then stalked out of the council. Afterwards, he and other militant leaders, including Ostenaco, gathered like-minded Cherokee from the Overhill, Valley, and Hill towns, and migrated to what is now the Chattanooga, Tennessee, area, to which Cameron had already transferred.

Christian's Virginia force found Great Island, Citico (Sitiku), Toqua (Dakwayi), Tuskegee (Taskigi), Chilhowee, and Great Tellico virtually deserted, with only the older leaders who had opposed the younger ones and their war remaining. Christian limited the destruction in the Overhill Towns to the burning of the deserted towns.

The Treaties of 1777

The next year, 1777, the Cherokee in the Hill, Valley, Lower, and Overhill towns signed the Treaty of Dewitt's Corner with Georgia and South Carolina (Ostenaco was one of the Cherokee signatories) and the Treaty of Fort Henry with Virginia and North Carolina promising to stop warring, with those colonies promising in return to protect them from attack. Dragging Canoe responded by raiding within fifteen miles of Fort Henry during the negotiations. One provision of the latter treaty required that James Robertson and a small garrison be quartered at Chota on the Little Tennessee.[15] Neither treaty actually halted attacks by frontiersmen from the illegal colonies, nor stop encroachment onto Cherokee lands. The peace treaty required the Cherokee give up their land of the Lower Towns in South Carolina and most of the area of the Out Towns.

First migration, to the Chickamauga area

In the meantime, Alexander Cameron had suggested to Dragging Canoe and his dissenting Cherokee that they settle at the place where the Great Indian Warpath crossed the Chickamauga River (South Chickamauga Creek), which was later known as the Chickamauga (Tsikamagi) Town under Big Fool. Since Dragging Canoe made that town his seat of operations, frontier Americans called his faction the "Chickamaugas".

As mentioned above, John McDonald already had a trading post there across the Chickamauga River, providing a link to Henry Stuart, brother of John, in the West Florida capital of Pensacola. Cameron, deputy Indian superintendent and blood brother to Dragging Canoe, accompanied him to Chickamauga. In fact, nearly all the whites legally resident among the Cherokee by their permission were part of the exodus.

In addition to Chickamauga Town, Dragging Canoe's band set up three other settlements on the Chickamauga River: Toqua (Dakwayi), at its mouth on the Tennessee River, Opelika, a few kilometers upstream from Chickamauga town, and Buffalo Town (Yunsayi; John Sevier called it Bull Town) at the headwaters of the river in northwest Georgia (in the vicinity of the later Ringgold, Georgia). Other towns were Cayuga (Cayoka) on Hiwassee Island; Black Fox (Inaliyi) at the current community of the same name in Bradley County, Tennessee; Ooltewah (Ultiwa), under Ostenaco on Ooltewah (Wolftever) Creek; Sawtee (Itsati), under Dragging Canoe's brother Little Owl on Laurel (North Chickamauga) Creek; Citico (Sitiku), along the creek of the same name; Chatanuga (Tsatanugi; not the same as the later city) at the foot of Lookout Mountain in what is now St. Elmo; and Tuskegee (Taskigi) under Bloody Fellow (Yunwigiga) on Williams' Island (which after the wars stretched across from the island southwest into Lookout Valley).

The land used by the Cherokee was once the traditional location of the Muscogee, who had withdrawn in the early 1700s to leave a buffer zone between themselves and the Cherokee. In the intervening years, the two tribes used the region as hunting grounds. When the Province of Carolina first began trading with the Cherokee in the late 1600s, their westernmost settlements were the twin towns of Great Tellico (Talikwa, same as Tahlequah) and Chatuga (Tsatugi) at the current site of Tellico Plains, Tennessee. The Coosawattee townsite (Kuswatiyi, for "Old Coosa Place"), reoccupied briefly by Big Mortar's Muscogee as mentioned above, was among the sites settled by the new influx of people.

Many Cherokee resented the (largely Scots-Irish) settlers moving into Cherokee lands, and agreed with Dragging Canoe. The Cherokee towns of Great Hiwassee (Ayuwasi), Tennessee (Tanasi), Chestowee (Tsistuyi), Ocoee (Ugwahi), and Amohee (Amoyee) in the vicinity of Hiwassee River were wholly in the camp of the rejectionists of the pacifism of the old chiefs, as were the Lower Cherokee in the North Georgia towns of Coosawatie (Kusawatiyi), Etowah (Itawayi), Ellijay (Elatseyi), Ustanari (or Ustanali), etc., who had been evicted from their homes in South Carolina by the Treaty of Dewitts' Corner. The Yuchi in the vicinity of the new settlement, on the upper Chickamauga, Pinelog, and Conasauga Creeks, likewise supported Dragging Canoe's policies.

The attacks in July 1776 proved to be Dragging Canoe's Methven; he had tried fighting in regular armies like whites, only to find guerrilla warfare more suitable. Based in their new homes, his main targets were settlers, whom he invariably referred to as "Virginians", on the Holston, Doe, Watauga, and Nolichucky Rivers, on the Cumberland and Red Rivers, and the isolated stations in between. They also ambushed parties travelling on the Tennessee River, and local sections of the many ancient trails that served as "highways", such as the Great Indian Warpath (Mobile to northeast Canada), the Cisca and St. Augustine Trail (St. Augustine to the French Salt Lick at Nashville), the Cumberland Trail (from the Upper Creek Path to the Great Lakes), and the Nickajack Trail (Nickajack to Augusta). Later, these Cherokee stalked the Natchez Trace and such highways as were constructed by the uninvited settlers like the Kentucky, Cumberland, and Walton Roads. Occasionally, the Cherokee attacked targets in Virginia, the Carolinas, Georgia, Kentucky, and the Ohio country.

Reaction

In 1778–1779, Savannah and Augusta, Georgia, were captured by the British with help from Dragging Canoe, John McDonald, and the Cherokee, who were being supplied with guns and ammunition through Pensacola and Mobile, and together they were able to gain control of parts of interior South Carolina and Georgia.

First invasion of the Chickamauga Towns

In early 1779, James Robertson of Virginia received warning from Chota that Dragging Canoe's warriors were going to attack the Holston area. In addition, he had received intelligence that John McDonald's place was the staging area for a conference of Indians Governor Hamilton was planning to hold at Detroit, and that a stockpile of supplies equivalent to that of a hundred packhorses was stored there.

In response, he ordered a preemptive assault under Evan Shelby (father of Isaac Shelby, first governor of the State of Kentucky) and John Montgomery. Boating down the Tennessee in a fleet of dugout canoes, they disembarked and destroyed the eleven towns in the immediate Chickamauga area and most of their food supply, along with McDonald's home and store. Whatever was not destroyed was confiscated and sold at the point where the trail back to the Holston crossed what has since been known as Sale Creek.

In the meantime, Dragging Canoe and John McDonald were leading the Cherokee and fifty Loyalist Rangers in attacks on Georgia and South Carolina, so there was no resistance and only four deaths among the towns' inhabitants. Upon hearing of the devastation of the towns, Dragging Canoe, McDonald, and their men, including the Rangers, returned to Chickamauga and its vicinity.

The Shawnee sent envoys to Chickamauga to find out if the destruction had caused Dragging Canoe's people to lose the will to fight, along with a sizable detachment of warriors to assist them in the South. In response to their inquiries, Dragging Canoe held up the war belts he'd accepted when the delegation visited Chota in 1776, and said, "We are not yet conquered".[16] To cement the alliance, the Cherokee responded to the Shawnee gesture with nearly a hundred of their warriors sent to the North.

The towns in the Chickamauga area were soon rebuilt and reoccupied by their former inhabitants. Dragging Canoe responded to the Shelby expedition with punitive raids on the frontiers of both North Carolina and Virginia.

Concord between the Lenape and the Cherokee

In spring 1779, Oconostota, Savanukah, and other non-belligerent Cherokee leaders travelled north to pay their respects after the death of the White Eyes, the Lenape leader who had been encouraging his people to give up their fighting against the Americans. He had also been negotiating, first with Lord Dunmore and second with the American government, for an Indian state with representatives seated in the Continental Congress, which he finally won an agreement for with that body, which he had addressed in person in 1776.

Upon the arrival of the Cherokee in the village of Goshocking, they were taken to the council house and began talks. The next day, the Cherokee present solemnly agreed with their "grandfathers" to take neither side in the ongoing conflict between the Americans and the British. Part of the reasoning was that thus "protected", neither tribe would find themselves subject to the vicissitudes of war. The rest of the world at conflict, however, remained heedless, and the provisions lasted as long as it took the ink to dry, as it were.[17][18]

Death of John Stuart

About this same time, John Stuart, up to that point Indian Affairs Superintendent, died at Pensacola. His deputy, Alexander Cameron, was assigned to the work with the Chickasaw and Choctaw and his replacement, Thomas Browne, assigned to the Cherokee, Muscogee, and Catawba. However, Cameron never went west and he and Browne worked together until the latter departed for St. Augustine.

The Chickasaw

The Chickasaw came into the war on the side of the British and their Indian allies in 1779 when George Rogers Clark and a party of over two hundred built Fort Jefferson and a surrounding settlement near the mouth of the Ohio, inside their hunting grounds. After learning of the trespass, the Chickasaw destroyed the settlement, laid siege to the fort, and began attacking the Kentucky frontier. They continued attacking the Cumberland and into Kentucky through the following year, their last raid in conjunction with Dragging Canoe's Cherokee, old animosities left over from the Cherokee-Chickasaw war of 1758-1769 forgotten in the face of the common enemy.

Cumberland Settlements

Later that year, Robertson and John Donelson traveled overland across country along the Kentucky Road and founded Fort Nashborough at the French Salt Lick (which got its name from having previously been the site of a French outpost called Fort Charleville) on the Cumberland River. It was the first of many such settlements in the Cumberland area, which subsequently became the focus of attacks by all the tribes in the surrounding region. Leaving a small group there, both returned east.

Early in 1780, Robertson and a group of fellow Wataugans left the east down the Kentucky Road headed for Fort Nashborough. Meanwhile, Donelson journeyed down the Tennessee with a party that included his family, intending to go across to the mouth of the Cumberland, then upriver to Ft. Nashborough. Eventually, the group did reach its destination, but only after being ambushed several times.

In the first encounter near Tuskegee Island, the Cherokee warriors under Bloody Fellow focused their attention on the boat in the rear whose passengers had come down with smallpox. There was only one survivor, later ransomed. The victory, however, proved to be a Pyrrhic one for the Cherokee, as the ensuing epidemic wiped out several hundred in the vicinity.

Several miles downriver, beginning with the obstruction known as the Suck or the Kettle, the party was fired upon throughout their passage through the Tennessee River Gorge (aka Cash Canyon), the party losing one with several wounded. Several hundred kilometers downriver, the Donelson party ran up against Muscle Shoals, where they were attacked at one end by the Muscogee and the other end by the Chickasaw. The final attack was by the Chickasaw in the vicinity of the modern Hardin County, Tennessee.

Shortly after the party's arrival at Fort Nashborough, Donelson, Robertson and others formed the Cumberland Compact.

John Donelson eventually moved to the Indiana country after the Revolution, where he and William Christian were captured while fighting in the Illinois country in 1786 and were burned at the stake by their captors.[19]

Augusta and King's Mountain

That summer, the new Indian superintendent, Thomas Browne, planned to have a joint conference between the Cherokee and Muscogee to plan ways to coordinate their attacks, but those plans were forestalled when the Americans made a concerted effort to retake Augusta, where he had his headquarters. The arrival of a war party from the Chickamauga Towns, joined by a sizable number or warriors from the Overhill Towns, prevented the capture of both, and they and Brown's East Florida Rangers chased Elijah Clarke's army into the arms of John Sevier, wreaking havoc on rebellious settlements along the way. This set the stage for the Battle of King's Mountain, in which loyalist militia under Patrick Ferguson moved south trying to encircle Clarke and were defeated by a force of 900 frontiersmen under Sevier and William Campbell referred to as the Overmountain Men.[20]

Alexander Cameron, aware of the absence from the settlements of nearly a thousand men, urged Dragging Canoe and other Cherokee leaders to strike while they had the opportunity. With Savanukah as their headman, the Overhill Towns gave their full support to the new offensive. Both Cameron and the Cherokee had been expecting a quick victory for Ferguson and were stunned he suffered such a resounding defeat so soon, but the assault was already in motion.

Hearing word of the new invasion from Nancy Ward, her second known betrayal, Virginia Governor Thomas Jefferson sent an expedition of seven hundred Virginians and North Carolinians against the Cherokee in December 1780, under the command of Sevier. It met a Cherokee war party at Boyd's Creek, and after the battle, joined by forces under Arthur Campbell and Joseph Martin, marched against the Overhill towns on the Little Tennessee and the Hiwassee, burning seventeen of them, including Chota, Chilhowee, the original Citico, Tellico, Great Hiwassee, and Chestowee. Afterwards, the Overhill leaders withdrew from further active conflict for the time being, though the Hill and Valley Towns continued to harass the frontier.

In the Cumberland area, the new settlements lost around forty people in attacks by the Cherokee, Muscogee, Chickasaw, Shawnee, and Lenape.[21]

Second migration and expansion

By 1781, Dragging Canoe was working with the towns of the Cherokee from western South Carolina relocated on the headwaters of the Coosa River, and with the Muscogee, particularly the Upper Muscogee. The Chickasaw, Shawnee, Huron, Mingo, Wyandot, and Munsee-Lenape (who were the first to do so) were repeatedly attacking the Cumberland settlements as well as those in Kentucky. Three months after the first Chickasaw attack on the Cumberland, the Cherokee's largest attack of the wars against those settlements came in April of that year, and culminated in what became known as the Battle of the Bluff, led by Dragging Canoe in person. Afterwards, settlers began to abandon the settlements until only three stations were left, a condition which lasted until 1785.[22]

Loss of British supply lines

In February 1780, Spanish forces from New Orleans under Bernardo de Galvez, allied to the Americans but acting in the interests of Spain, captured Mobile in the Battle of Fort Charlotte. When they next moved against Pensacola the following month, William McIntosh, one of John Stuart's agents and father of the later Muscogee leader William McIntosh (Tustunnugee Hutkee), and Alexander McGillivray (Hoboi-Hili-Miko) rallied 2000 Muscogee warriors to its defense. A British fleet arrived before the Spanish could take the port. A year later, the Spanish reappeared with an army twice the size of the garrison of British, Choctaw, and Muscogee defenders, and Pensacola fell two months later. Shortly thereafter, Savannah and Augusta were also retaken by the revolutionaries.[23]

Politics in the Overhill Towns

In the fall of 1781, the British engineered a coup d'état of sorts that put Savanukah as First Beloved Man in place of the more pacifist Oconostota, who succeeded Attakullakulla. For the next year or so, the Overhill Cherokee openly, as they had been doing covertly, supported the efforts of Dragging Canoe and his Cherokee. In the fall of 1782, however, the older pacifist leaders replaced him with another of their number, Corntassel (Kaiyatsatahi, known to history as "Old Tassel"), and sent messages of peace along with complaints of settler encroachment to Virginia and North Carolina.[24] Opposition from pacifist leaders, however, never stopped war parties from traversing the territories of any of the town groups, largely because the average Cherokee supported their cause, nor did it stop small war parties of the Overhill Towns from raiding settlements in East Tennessee, mostly those on the Holston.

Cherokee in the Ohio region

A party of Cherokee joined the Lenape, Shawnee, and Chickasaw in a diplomatic visit to the Spanish at Fort St. Louis in the Missouri country in March 1782 seeking a new avenue of obtaining arms and other assistance in the prosecution of their ongoing conflict with the Americans in the Ohio Valley. One group of Cherokee at this meeting led by Standing Turkey sought and received permission to settle in Spanish Louisiana, in the region of the White River.[25]

By 1783, there were at least three major communities of Cherokee in the region. One lived among the Chalahgawtha (Chillicothe) Shawnee. The second Cherokee community lived among the mixed Wyandot-Mingo towns on the upper Mad River near the later Zanesfield, Ohio.[26] A third group of Cherokee is known to have lived among and fought with the Munsee-Lenape, the only portion of the Lenape nation at war with the Americans.[27]

Second invasion of the Chickamauga Towns

In September 1782, an expedition under Sevier once again destroyed the towns in the Chickamauga vicinity, though going no further west than the Chickamauga River, and those of the Lower Cherokee down to Ustanali (Ustanalahi), including what he called Vann's Town. The towns were deserted because having advanced warning of the impending attack, Dragging Canoe and his fellow leaders chose relocation westward. Meanwhile, Sevier's army, guided by John Watts, somehow never managed to cross paths with any parties of Cherokee.

Dragging Canoe and his people established what whites called the Five Lower Towns downriver from the various natural obstructions in the twenty-six-mile Tennessee River Gorge. Starting with Tuskegee (aka Brown's or Williams') Island and the sandbars on either side of it, these obstructions included the Tumbling Shoals, the Holston Rock, the Kettle (or Suck), the Suck Shoals, the Deadman's Eddy, the Pot, the Skillet, the Pan, and, finally, the Narrows, ending with Hale's Bar. The whole twenty-six miles was sometimes called The Suck, and the stretch of river was notorious enough to merit mention even by Thomas Jefferson.[28] These navigational hazards were so formidable, in fact, that the French agents attempting to travel upriver to reach Cherokee country during the French and Indian War, intending to establish an outpost at the spot later occupied by British agent McDonald, gave up after several attempts.

The Five Lower Towns

The Five Lower Towns included Running Water (Amogayunyi), at the current Whiteside in Marion County, Tennessee, where Dragging Canoe made his headquarters; Nickajack (Ani-Kusati-yi, or Koasati place), eight kilometers down the Tennessee River in the same county; Long Island (Amoyeligunahita), on the Tennessee just above the Great Creek Crossing; Crow Town (Kagunyi) on the Tennessee, at the mouth of Crow Creek; and Stecoyee (Utsutigwayi, aka Lookout Mountain Town), at the current site of Trenton, Georgia. Tuskegee Island Town was reoccupied as a lookout post by a small band of warriors to provide advance warning of invasions, and eventually many other settlements in the area were resettled as well.

Because this was a move into the outskirts of Muscogee territory, Dragging Canoe, knowing such a move might be necessary, had previously sent a delegation under Little Owl to meet with Alexander McGillivray, the major Muscogee leader in the area, to gain their permission to do so. When he and his followers moved their base, so too did the British representatives Cameron and McDonald, making Running Water the center of their efforts throughout the Southeast. The Chickasaw were in the meantime trying to play off the Americans and the Spanish against each other with little interest in the British. Turtle-at-Home (Selukuki Woheli), another of Dragging Canoe's brothers, along with some seventy warriors, headed north to live and fight with the Shawnee.

Cherokee continued to migrate westward to join Dragging Canoe's followers, whose ranks were further swelled by runaway slaves, white Tories, Muscogee, Koasati, Kaskinampo, Yuchi, Natchez, and Shawnee, as well as a band of Chickasaw living at what was later known as Chickasaw Old Fields across from Guntersville, plus a few Spanish, French, Irish, and Germans.

Later major settlements of the Lower Cherokee (as were they called after the move) included Willstown (Titsohiliyi) near the later Fort Payne; Turkeytown (Gundigaduhunyi), at the head of the Cumberland Trail where the Upper Creek Path crossed the Coosa River near Centre, Alabama; Creek Path (Kusanunnahiyi), near at the intersection of the Great Indian Warpath with the Upper Creek Path at the modern Guntersville, Alabama; Turnip Town (Ulunyi), seven miles from the present-day Rome, Georgia; and Chatuga (Tsatugi), nearer the site of Rome.

This expansion came about largely because of the influx of Cherokee from North Georgia, who fled the depredations of expeditions such as those of Sevier; a large majority of these were former inhabitants of the Lower Towns in northeast Georgia and western South Carolina. Cherokee from the Middle, or Hill, Towns also came, a group of whom established a town named Sawtee (Itsati) at the mouth of South Sauta Creek on the Tennessee. Another town, Coosada, was added to the coalition when its Koasati and Kaskinampo inhabitants joined Dragging Canoe's confederation. Partly because of the large influx from North Georgia added to the fact that they were no longer occupying the Chickamauga area as their main center, Dragging Canoe's followers and others in the area began to be referred to as the Lower Cherokee, with he and his lieutenants remaining in the leadership.

Another visit from the North

In November 1782, twenty representatives from four northern tribes--Wyandot, Ojibwa, Ottawa, and Potowatami--travelled south to consult with Dragging Canoe and his lieutenants at his new headquarters in Running Water Town, which was nestled far back up the hollow from the Tennessee River onto which it opened. Their mission was to gain the help of Dragging Canoe's Cherokee in attacking Pittsburgh and the American settlements in Kentucky and the Illinois country.[29]

After the Revolution

Eventually, Dragging Canoe realized the only solution for the various Indian nations to maintain their independence was to unite in an alliance against the Americans. In addition to increasing his ties to McGillivray and the Upper Muscogee, with whom he worked most often and in greatest numbers, he continued to send his warriors to fighting alongside the Shawnee, Choctaw, and Lenape.

In January 1783, Dragging Canoe travelled to St. Augustine, the capital of East Florida, for a summit meeting with a delegation of northern tribes, and called for a federation of Indians to oppose the Americans and their frontier colonists. Browne, the British Indian Superintendent, approved the concept. At Tuckabatchee a few months later, a general council of the major southern tribes (Cherokee, Muscogee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, and Seminole) plus representatives of smaller groups (Mobile, Catawba, Biloxi, Huoma, etc.) took place to follow up, but plans for the federation were cut short by the signing of the Treaty of Paris. In June, Browne received orders from London to cease and desist.[30]

Following that treaty, Dragging Canoe turned to the Spanish (who still claimed all the territory south of the Cumberland and were now working against the Americans) for support, trading primarily through Pensacola and Mobile. What made this possible was that fact that the Spanish governor of Louisiana Territory in New Orleans had taken advantage of the British setback to seize those ports. Dragging Canoe maintained relations with the British governor at Detroit, Alexander McKee, through regular diplomatic missions there under his brothers Little Owl and The Badger (Ukuna).

Chickasaw and Muscogee treaties

In November, the Chickasaw signed the Treaty of French Lick with the new United States of America that year and never again took up arms against it. The Lower Cherokee were also present at the conference and apparently made some sort of agreement to cease their attacks on the Cumberland for after this Americans settlements in the area began to grow again.[31] That same month, the pro-American camp in the Muscogee nation signed the Treaty of Augusta with the State of Georgia, enraging McGillivray, who wanted to keep fighting; he burned the houses of the leaders responsible and sent warriors to raid Georgia settlements.[32]

Treaties of Hopewell and Coyatee

The Cherokee in the Overhill, Hill, and Valley Towns also signed a treaty with the new United States government, the 1785 Treaty of Hopewell, but in their case it was a treaty made under duress, the frontier colonials by this time having spread further along the Holston and onto the French Broad. Several leaders from the Lower Cherokee signed, including two from Chickamauga Town (which had been rebuilt) and one from Stecoyee. None of the Lower Cherokee, however, had any part in the Treaty of Coyatee, which new State of Franklin forced Corntassel and the other Overhill leaders to sign at gunpoint, ceding the remainder of the lands north of the Little Tennessee. Nor did they have any part in the Treaty of Dumplin Creek, which ceded the remaining land within the claimed boundaries of Sevier County. The colonials could now shift military forces to Middle Tennessee in response to increasing frequency of attacks by both Chickamauga Cherokee (by now usually called Lower Cherokee) and Upper Muscogee.

State of Franklin

In May 1785, the settlements of Upper East Tennessee, then comprising four counties of western North Carolina, petitioned the Congress of the Confederation to be recognized as the "State of Franklin". Even though their petition failed to receive the two-thirds votes necessary to qualify, they proceeded to organize what amounted to a secessionist government, holding their first "state" assembly in December 1785. One of their chief motives was to retain the foothold they had recently gained in the Cumberland Basin.

Attacks on the Cumberland

In the summer of 1786, Dragging Canoe and his warriors along with a large contingent of Muscogee raided the Cumberland region, with several parties raiding well into Kentucky. John Sevier responded with a punitive raid on the Overhill Towns. One such occasion that summer was notable for the fact that the raiding party was led by none other than Hanging Maw of Coyatee, who was supposedly friendly at the time.

Formation of the Western Confederacy

In addition to the small bands still operating with the Shawnee, Wyandot-Mingo, and Lenape in the Northwest, a large contingent of Cherokee led by The Glass attended and took an active role in a grand council of northern tribes (plus some Muscogee and Choctaw in addition to the Cherokee contingent) resisting the American advance into the western frontier which took place in November–December 1786 in the Wyandot town of Upper Sandusky just south of the British capital of Detroit.[33]

This meeting, initiated by Joseph Brant (Thayendanegea), the Mohawk leader who was head chief of the Iroquois Six Nations and like Dragging Canoe fought on the side of the British during the American Revolution, led to the formation of the Western Confederacy to resist American incursions into the Old Northwest. Dragging Canoe and his Cherokee were full members of the Confederacy. The purpose of the Confederacy was to coordinate attacks and defense in the Northwest Indian War of 1785-1795.

According to John Norton (Teyoninhokovrawen), Brant's adopted son, it was here that The Glass formed a friendship with his adopted father that lasted well into the 19th century.[34] He apparently served as Dragging Canoe's envoy to the Iroquois as the latter's brothers did to McKee and to the Shawnee.

The passage of the Northwest Ordinance by the Congress of the Confederation (subsequently affirmed by the United States Congress) in 1787, establishing the Northwest Territory and essentially giving away the land upon which they lived, only exacerbated the resentment of the tribes in the region.

Coldwater Town

The settlement of Coldwater was founded by a party of French traders who had come down for the Wabash to set up a trading center in 1783. It sat a few miles below the foot of the thirty-five mile long Muscle Shoals, near the mouth of Coldwater Creek and about three hundred yards back from the Tennessee River, close the site of the modern Tuscumbia, Alabama. For the next couple of years, trade was all the French did, but then the business changed hands. Around 1785, the new management began covertly gathering Cherokee and Muscogee warriors into the town, whom they then encouraged to attack the American settlements along the Cumberland and its environs. The fighting contingent eventually numbered approximately nine Frenchmen, thirty-five Cherokee, and ten Muscogee.

Because the townsite was well-hidden and its presence unannounced, James Robertson, commander of the militia in the Cumberland's Davidson and Sumner Counties, at first accused the Lower Cherokee of the new offensives. In 1787, he marched his men to their borders in a show of force, but without an actual attack, then sent an offer of peace to Running Water. In answer, Dragging Canoe sent a delegation of leaders led by Little Owl to Nashville under a flag of truce to explain that his Cherokee were not the responsible parties.

Meanwhile, the attacks continued. At the time of the conference in Nashville, two Chickasaw out hunting game along the Tennessee in the vicinity of Muscle Shoals chanced upon Coldwater Town, where they were warmly received and spent the night. Upon returning home to Chickasaw Bluffs, now Memphis, Tennessee, they immediately informed their head man, Piomingo, of their discovery. Piomingo then sent runners to Nashville.

Just after these runners had arrived in Nashville, a war party attacked one of its outlying settlements, killing Robertson's brother Mark. In response, Robertson raised a group of one hundred fifty volunteers and proceeded south by a circuitous land route, guided by two Chickasaw. Somehow catching the town offguard despite the fact they knew Robertson's force was approaching, they chased its would-be defenders to the river, killing about half of them and wounding many of the rest. They then gathered all the trade goods in the town to be shipped to Nashville by boat, burned the town, and departed.[35]

After the wars, it became the site of Colbert's Ferry, owned by Chickasaw leader George Colbert, the crossing place over the Tennessee River of the Natchez Trace.

Muscogee council at Tuckabatchee

In 1786, McGillivray had convened a council of war at the dominant Upper Muscogee town of Tuckabatchee about recent incursions of Americans into their territory. The council decided to go on the warpath against the trespassers, starting with the recent settlements along the Oconee River. McGillivray had already secured support from the Spanish in New Orleans.

The following year, because of the perceived insult of the incursion Cumberland against Coldwater so near to their territory, the Muscogee also took up the hatchet against the Cumberland settlements. They continued their attacks until 1789, but the Cherokee did not join them for this round due partly to internal matters but more because of trouble from the State of Franklin.

Peak of Lower Cherokee power and influence

Dragging Canoe's last years, 1788–1792, were the peak of his influence and that of the rest of the Lower Cherokee, among the other Cherokee and among other Indian nations, both south and north, as well as with the Spanish of Pensacola, Mobile, and New Orleans, and the British in Detroit. He also sent regular diplomatic envoys to negotiations in Nashville, Jonesborough then Knoxville, and Philadelphia.

Massacre of the Kirk family

In May 1788, a party of Cherokee from Chilhowee came to the house of John Kirk's family on Little River, while he and his oldest son, John Jr., were out. When Kirk and John Jr. returned, they found the other eleven members of their family dead and scalped.

Massacre of the Brown family

After a preliminary trip to the Cumberland at the end of which he left two of his sons to begin clearing the plot of land at the mouth of White's Creek, James Brown returned to North Carolina to fetch the rest of the family, with whom he departed Long-Island-on-the-Holston by boat in May 1788. When they passed by Tuskegee Island five days later, Bloody Fellow stopped them, looked around the boat, then let them proceed, meanwhile sending messengers ahead to Running Water.

Upon the family's arrival at Nickajack, a party of forty under mixed-blood John Vann boarded the boat and killed Col. Brown, his two older sons on the boat, and five other young men travelling with the family. Mrs. Brown, the two younger sons, and three daughters were taken prisoner and distributed to different families.

When he learned of the massacre the following day, The Breath (Unlita), Nickajack's headman, was seriously displeased. He later adopted into his own family the Browns' son Joseph as a son, who had been originally given to Kitegisky (Tsiagatali), who had first adopted him as a brother, treating him well, and of whom Joseph had fond memories in later years.

Mrs. Brown and one of her daughters were given to the Muscogee and ended up the personal household of Alexander McGillivray. George, the elder of the surviving sons, also ended up with the Muscogee, but elsewhere. Another daughter went to a Cherokee nearby Nickajack and the third to a Cherokee in Crow Town.[36]

Murders of the Overhill chiefs

At the beginning of June 1788, John Sevier, now no longer governor of the State of Franklin, raised a hundred volunteers in June of that year and set out for the Overhill Towns. After a brief stop at the Little Tennessee, the group went to Great Hiwassee and burned it to the ground. Returning to Chota, Sevier send a detachment under James Hubbard to Chilhowee to punish those responsible for the Kirk massacre, John Kirk Jr. among them. Hubbard brought along Corntassel and Hanging Man from Chota.

At Chilhowee, Hubbard raised a flag of truce, took Corntassel and Hanging Man to the house of Abraham, still headman of Chilhowee, who was there with his son, also bringing along Long Fellow and Fool Warrior. Hubbard posted guards at the door and windows of the cabin, and gave John Kirk Jr. a tomahawk to get his revenge.

The murder of the pacifist Overhill chiefs under a flag of truce angered the entire Cherokee nation and resulted in those previously reluctant taking the warpath, an increase in hostility that lasted for several months. Doublehead, Corntassel's brother, was particularly incensed.

Highlighting the seriousness of the matter, Dragging Canoe came in to address the general council of the Nation, now meeting at Ustanali on the Coosawattee River (one of the former Lower Towns on the Keowee River relocated to the vicinity of Calhoun, Georgia) to which the seat of the council had been moved, along with the election of Little Turkey (Kanagita) as First Beloved Man, an election contested by Hanging Maw of Coyatee (who had been elected chief headman of the traditional Overhill Towns on the Little Tennessee River), to succeed the murdered chief. Interestingly, both men had been among those who originally followed Dragging Canoe into the southwest of the nation, with Hanging Maw known to have been on the warpath at least as late as 1786.

Dragging Canoe's presence at the Ustanali council and the council's meetings now held in what was then the area of the Lower Towns (but to which Upper Cherokee from the Overhill towns were migrating in vast numbers), as well as his acceptance of the election of his former co-belligerent Little Turkey as principal leader over all the Cherokee nation, are graphic proof that he and his followers remained Cherokee and were not a separate tribe as some, following Brown, allege.

Houston's Station

In early August, the commander of the garrison at Houston's Station (near the present Maryville, Tennessee) received word that a Cherokee force of nearly five hundred was planning to attack his position. He therefore sent a large reconnaissance patrol to the Overhill Towns.

Stopping in the town of Citico on the south side of the Little Tennessee, which they found deserted, the patrol scattered throughout the town's orchard and began gathering fruit. Six of them died in the first fusilade, another ten while attempting to escape across the river.

With the loss of those men, the garrison at Houston's Station was seriously beleaguered. Only the arrival of a relief force under John Sevier saved the fort from being overrun and its inhabitants slaughtered. With the garrison joining his force, Sevier marched to the Little Tennessee and burned Chilhowee.

Invasion and counter-invasion

Later in August, Joseph Martin (who was married to Betsy, daughter of Nancy Ward, and living at Chota), with 500 men, marched to the Chickamauga area, intending to penetrate the edge of the Cumberland Mountains to get to the Five Lower Towns. He sent a detachment to secure the pass over the foot of Lookout Mountain (Atalidandaganu), which was ambushed and routed by a large party of Dragging Canoe's warriors, with the Cherokee in hot pursuit.[37] One of the participants later referred to the spot as "the place where we made the Virginians turn their backs".[38] According to one of the participants on the other side, Dragging Canoe, John Watts, Bloody Fellow, Kitegisky, The Glass, Little Owl, and Dick Justice were all present at the encounter.[39]

The army of Cherokee warriors Dragging Canoe raised in response reached three thousand in total, split into warbands hundreds strong each. One of these warbands was headed by John Watts (Kunnessee-i; also known as 'Young Tassel') with Bloody Fellow, Kitegisky (Tsiagatali), and The Glass, and included a young warrior named or Pathkiller (Nunnehidihi), later known as The Ridge (Ganundalegi).

In October of that year, the band advanced across country toward White's Fort. Along the way, they attacked Gillespie's Station on the Holston River after capturing settlers who had left the enclosure to work in the fields, storming the stockade when the defender's ammunition ran out, killing the men and some of the women and taking twenty-eight women and children prisoner. They then proceeded to attack White's Fort and Houston's Station only to be beaten back.[40][41] Afterwards, the warband wintered at an encampment on the Flint River in present day Unicoi County, Tennessee as a base of operations.[42]

In return, punishment attacks by the settlers' militia increased. Troops under Sevier destroyed the Valley Towns in North Carolina. At Ustalli, on the Hiwassee, the population had been evacuated by Cherokee warriors led by Bob Benge, who left a rearguard to ensure their escape. After lighting the town, Sevier and his group pursued its fleeing inhabitants, but were ambushed at the mouth of the Valley River by Benge's party. From there they went to the village of Coota-cloo-hee (Gadakaluyi) and proceeded to burn down its cornfields, but were chased off by 400 warriors led by John Watts (Young Tassel).[43][44]

One result of the above destruction is that the Overhill Cherokee and the refugees from other parts of the nation among them all but completely abandoned the settlements on the Little Tennessee and dispersed south and west, with Chota being virtually the only town left with any inhabitants.

The Flint Creek band/Prisoner exchange

John Watts' band on Flint Creek fell upon serious misfortune early the next year. In early January 1789, they were surrounded by a force under John Sevier that was equipped with grasshopper cannons. The gunfire from the Cherokee was so intense, however, that Sevier abandoned his heavy weapons and ordered a cavalry charge that led to savage hand-to-hand fighting. Watt's band lost nearly 150 warriors.[45]

Word of their defeat did not reach Running Water until April, when it arrived with an offer from Sevier for an exchange of prisoners which specifically mentioned the surviving members of the Brown family, including Joseph, who had been adopted first by Kitegisky and later by The Breath.[46] Among those captured at Flint Creek were Bloody Fellow and Little Turkey's daughter.[47]

Joseph and his sister Polly were brought immediately to Running Water, but when runners were sent to Crow Town to retrieve Jane, their youngest sister, her owner refused to surrender her. Bob Benge, present in Running Water at the time, he mounted his horse and hefted his famous axe, saying, "I will bring the girl, or the owner's head". The next morning he returned with Jane.[48] The three were handed over to Sevier at Coosawattee.

McGillivray delivered Mrs. Brown and Elizabeth to her son William during a trip to Rock Landing, Georgia, in November. George, the other surviving son from the trip, remained with the Muscogee until 1798.[49]

Blow to the Western Confederacy

In January 1789, Arthur St. Clair, American governor of the Northwest Territory, concluded two separate peace treaties with members of the Western Confederacy. The first was with the Iroquois, except for the Mohawk, and the other was with the Wyandot, Lenape, Ottawa, Potawotami, Sac, and Ojibway. The Mohawk, the Shawnee, the Miami, and the tribes of the Wabash Confederacy, who had been doing most of the fighting, not only refused to go along but became more aggressive, especially the Wabash tribes.[50]

Chiksika's band of Shawnee

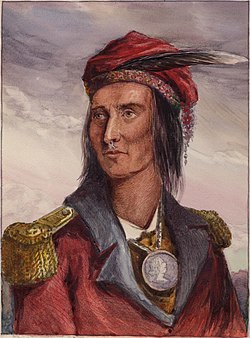

In early 1789, a band of thirteen Shawnee arrived in Running Water after spending several months hunting in the Missouri River country, led by Chiksika, a leader contemporary with the famous Blue Jacket (Weyapiersenwah). In the band was his brother, the later leader Tecumseh.

Their mother, a Muscogee, had left the north (her husband died at the Battle of Point Pleasant, the only major action of Dunmore's War, in 1774) and gone to live in her old town because without her husband she was homesick. The town was now near those of the Cherokee in the Five Lower Towns. Their mother had died, but Chiksika's Cherokee wife and his daughter were living at nearby Running Water Town, so they stayed.

They were warmly received by the Cherokee warriors, and, based out of Running Water, they participated in and conducted raids and other actions, in some of which Cherokee warriors participated (most notably Bob Benge). Chiksika was killed in one of the actions in their band took part in April, resulting in Tecumseh becoming leader of the small Shawnee band, gaining his first experiences as a leader in warfare.

The band remained at Running Water until late 1790, then returned north, having been long gone.[51][52]

The "Miro Conspiracy"

Starting in 1786, the leaders of the State of Franklin and the Cumberland District began secret negotiations with Esteban Rodriguez Miro, governor of Spanish Louisiana, to deliver their regions to the jurisdiction of the Spanish Empire. Those involved included James Robertson, Daniel Smith, and Anthony Bledsoe of the Cumberland District, John Sevier and Joseph Martin of the State of Franklin, James White, recently-appointed American Superintendent for Southern Indian Affairs (replacing Thomas Browne), and James Wilkinson of Kentucky.

The irony lay in the fact that the Spanish backed the Cherokee and Muscogee harassing their territories. Their main counterpart on the Spanish side in New Orleans was Diego de Gardoqui. Gardoqui's negotiations with Wilkinson, initiated by the latter, to bring Kentucky into the Spanish orbit also were separate but simultaneous.

The "conspiracy" went as far as the Franklin and Cumberland officials promising to take the oath of loyalty to Spain and renounce allegiance to any other nation. Robertson went as far as having the North Carolina assembly create the "Mero District" out of the three Cumberland counties (Davidson, Sumner, Tennessee). There was even a convention held in the failing State of Franklin on the question, and those present voted in its favor.

A large part of their motivation, besides the desire to secede from North Carolina, was the hope that this course of action would bring relief from Indian attacks. The series of negotiations involved McGillivray, with Roberston and Bledsoe writing him of the Mero District's peaceful intentions toward the Muscogee and simultaneously sending White as emissary to Gardoqui to convey news of their overture.[53]

The scheme fell apart for two main reasons. The first was the dithering of the Spanish government in Madrid. The second was the interception of a letter from Joseph Martin which fell into the hands of the Georgia legislature in January 1789.

North Carolina, to which the western counties in question belonged under the laws of the United States, took the simple expedient of ceding the region to the federal government, which established the Southwest Territory in May 1790. Of note is the fact that under the new regime the Mero District kept its name.

Wilkinson remained a paid Spanish agent until his death in 1825, including his years as one of the top generals in the U.S. army, and was involved in the Aaron Burr conspiracy. Ironically, he became the first American governor of Louisiana Territory in 1803.

Doublehead

The opposite end of Muscle Shoals from Coldwater Town, mentioned above, was occupied in 1790 by a roughly forty-strong party under the infamous Doublehead (Taltsuska), plus their families. He had gained permission to establish his town at the head of the Shoals, which was in Chickasaw territory, because the local headman, George Colbert, the mixed-blood leader who later owned Colbert's Ferry at the foot of Muscle Shoals, was his son-in-law.

Like that of the former Coldwater Town, Doublehead's Town was mixed, with Cherokee, Muscogee, Shawnee, and a few Chickasaw, and quickly grew beyond the initial forty warriors, who carried out many small raids against the Cumberland and into Kentucky. During one of the more notable of these forays in June 1792, his warriors ambushed a canoe carrying the three sons of Valentine Sevier (brother of John) and three others out on a scouting expedition searching for his party, killing the three Seviers and another of the expedition, with two escaping.

Doublehead conducted his operations largely independent of the Lower Cherokee, though he did take part in large operations with them on occasion, such as the invasion of the Cumberland in 1792 and that of the Holston in 1793.[54]

Treaty of New York

Dragging Canoe's long-time ally among the Muscogee, Alexander McGillivray, led a delegation of twenty-seven leaders north, where they signed the Treaty of New York in August 1790 with the United States government on behalf of the "Upper, Middle, and Lower Creek and Seminole composing the Creek nation of Indians". However, the signers did not represent even half the Muscogee Confederacy, and there was much resistance to the treaty from the peace faction he had attacked after the Treaty of Augusta as well as the faction of the Confederacy who wished to continue the war and did so.

Muscle Shoals

In January 1791, a group of land speculators named the Tennessee Company from the Southwest Territory led by James Hubbard and Peter Bryant attempted to gain control of the Muscle Shoals and its vicinity by building a settlement and fort at the head of the Shoals. They did so against an executive order of President Washington forbidding it, as relayed to them by the governor of the Southwest Territory, William Blount. The Glass came down from Running Water with sixty warriors and descended upon the defenders, captained by Valentine Sevier, brother of John, told them to leave immediately or be killed, then burned their blockhouse as they departed.[55]

Bob Benge

Starting in 1791, Benge, and his brother The Tail (Utana; aka Martin Benge), based at Willstown, began leading attacks against settlers in East Tennessee, Southwest Virginia, and Kentucky, often in conjunction with Doublehead and his warriors from Coldwater. Eventually, he became one of the most feared warriors on the frontier.[56]

Meanwhile, Muscogee scalping parties began raiding the Cumberland settlements again, though without mounting any major campaigns.

Treaty of Holston

The Treaty of Holston, signed in July 1791, required from the Upper Towns more land in return for continued peace because the government proved unable to stop or roll back illegal settlements. However, it also seemed to guarantee Cherokee sovereignty and led the Upper Cherokee chiefs to believe they had the same status as states. Several representatives of the Lower Cherokee in the negotiations and signed the treaty, including John Watts, Doublehead, Bloody Fellow, Black Fox (Dragging Canoe's nephew), The Badger (his brother), and Rising Fawn (Agiligina; aka George Lowery).

Battle of the Wabash

Later in the summer, a small delegation of Cherokee under Dragging Canoe's brother Little Owl traveled north to meet with the Indian leaders of the Western Confederacy, chief among them Blue Jacket (Weyapiersenwah) of the Shawnee, Little Turtle (Mishikinakwa) of the Miami, and Buckongahelas of the Lenape. While they were there, word arrived at Running Water that Arthur St. Clair, governor of the Northwest Territory, was planning an invasion against the allied tribes in the north. Little Owl immediately sent word south.

Dragging Canoe quickly sent a 30-strong war party north under his brother The Badger, where, along with the warriors of Little Owl and Turtle-at-Home they participated in the decisive encounter in November 1791 known as the Battle of the Wabash, the worst defeat ever inflicted by Native Americans upon the American military, the American military body count of which far surpassed that at the more famous Battle of the Little Bighorn in 1876.

After the battle, Little Owl, The Badger, and Turtle-at-Home returned south with most of the warriors who'd accompanied the first two. The warriors who'd come north years earlier, both with Turtle-at-Home and a few years before, remained in the Ohio region, but the returning warriors brought back a party of thirty Shawnee under the leadership of one known as Shawnee Warrior that frequently operated alongside warriors under Little Owl.

Death of "the savage Napoleon"

Inspired by news of the northern victory, Dragging Canoe embarked on a mission to unite the native people of his area as had Little Turtle and Blue Jacket, visiting the other major tribes in the region. His embassies to the Lower Muscogee and the Choctaw were successful, but the Chickasaw in West Tennessee refused his overtures. Upon his return, which coincided with that of The Glass and Dick Justice (Uwenahi Tsusti), and of Turtle-at-Home, from successful raids on settlements along the Cumberland (in the case of the former two) and in Kentucky (in the case of the latter), a huge all-night celebration was held at Stecoyee at which the Eagle Dance was performed in his honor.

By morning, March 1, 1792, Dragging Canoe was dead. A procession of honor carried his body to Running Water, where he was buried. By the time of his death, the resistance of the Chickamauga/Lower Cherokee had led to grudging respect from the settlers, as well as the rest of the Cherokee nation. He was even memorialized at the general council of the Nation held in Ustanali in June by his nephew Black Fox (Inali):

The Dragging Canoe has left this world. He was a man of consequence in his country. He was friend to both his own and the white people. His brother [Little Owl] is still in place, and I mention it now publicly that I intend presenting him with his deceased brother's medal; for he promises fair to possess sentiments similar to those of his brother, both with regard to the red and the white. It is mentioned here publicly that both red and white may know it, and pay attention to him.[58]

The final years

The last years of the Chickamauga wars saw John Watts, who had spent much of the wars affecting friendship and pacifism towards his American counterparts while living most of the time among the Overhill Cherokee, drop his facade as he took over from his mentor, though deception and artifice still formed part of his diplomatic repertoire.

John Watts

At his own previous request, the old warrior was succeeded as leader of the Lower Cherokee by John Watts (Kunokeski), although The Bowl (Diwali) succeeded him as headman of Running Water,[59] along with Bloody Fellow and Doublehead, who continued Dragging Canoe's policy of Indian unity, including an agreement with McGillivray of the Upper Muscogee to build joint blockhouses from which warriors of both tribes could operate at the junction of the Tennessee and Clinch Rivers, at Running Water, and at Muscle Shoals.

Watts, Tahlonteeskee, and 'Young Dragging Canoe' (whose actual name was Tsula, or "Red Fox") travelled to Pensacola in May at the invitation of Arturo O'Neill, Spanish governor of West Florida. They took with them letters of introduction from John McDonald. Once there, they forged a treaty with O'Neill for arms and supplies with which to carry on the war.[60] Upon returning north, Watts moved his base of operations to Willstown in order to be closer to his Muscogee allies and his Spanish supply line.

Watts at the time of Dragging Canoe's death had been serving as an interpreter during negotiations in Chota between the American government and the Overhill Cherokee. Throughout the wars, up until the time he became principal chief of the Lower Cherokee, he continued to live in the Overhill Towns as much as much as in the Chickamauga and Lower Towns, and many whites mistook him for a non-belligerent, most notably John Sevier when he mistakenly contracted Watts to guide him to Dragging Canoe's headquarters in September 1782.

Meanwhile John McDonald, now British Indian Affairs Superintendent, moved to Turkeytown with his assistant Daniel Ross and their families. Some of the older chiefs, such as The Glass of Running Water, The Breath of Nickajack, and Dick Justice of Stecoyee, abstained from active warfare but did nothing to stop the warriors in their towns from taking part in raids and campaigns.

That summer, the band of Shawnee Warrior and the party of Little Owl began joining the raids of the Muscogee on the Mero District. In late June, they attacked a small fortified settlement called Ziegler's Station, swarming it, killing the men and taking the women and children prisoner.[61]

Buchanan's Station

In September 1792, Watts orchestrated a large campaign intending to attack the Holston region with a large combined army in four bands of two hundred each. When the warriors were mustering at Stecoyee, however, he learned that their planned attack was expected and decided to aim for Nashville instead.

The army Watts led into the Cumberland region was nearly a thousand strong, including a contingent of cavalry. It was to be a four-pronged attack in which Tahlonteeskee (Ataluntiski; Doublehead's brother) and Bob Benge's brother The Tail led a party to ambush the Kentucky Road, Doublehead with another to the Cumberland Road, and Middle Striker (Yaliunoyuka) led another to do the same on the Walton Road, while Watts himself led the main force, made up of 280 Cherokee, Shawnee, and Muscogee warriors plus cavalry, intending to go against the fort at Nashville.

He sent out George Fields (Unegadihi; "Whitemankiller") and John Walker, Jr. (Sikwaniyoha) as scouts ahead of the army, and they killed the two scouts sent out by James Robertson from Nashville.

Near their target on the evening of 30 September, Watts's combined force came upon a small fort known as Buchanan's Station. Talotiskee, leader of the Muscogee, wanted to attack it immediately, while Watts argued in favor of saving it for the return south. After much bickering, Watts gave in around midnight. The assault proved to be a disaster for Watts. He himself was wounded, and many of his warriors were killed, including Talotiskee and some of Watts' best leaders; Shawnee Warrior, Kitegisky, and Dragging Canoe's brother Little Owl were among those who died in the encounter.

Doublehead's group of sixty ambushed a party of six and took one scalp then headed for toward Nashville. On their way, they were attacked by a militia force and lost thirteen men, and only heard of the disaster at Buchanan's Station afterwards. Tahlonteeskee's party, meanwhile, stayed out into early October, attacking Black's Station on Crooked Creek, killing three, wounding more, and capturing several horses. Middle Striker's party was more successful, ambushing a large armed force coming to the Mero District down the Walton Road in November and routing it completely without losing a single man.[62][63]